Discover the Non-Goals of TypeScript

The goals of TypeScript are obvious, but do you know about its non-goals?

Since its inception, TypeScript has had clearly defined design goals.

But did you know that TypeScript also has a set of non-goals? Let’s discuss each of those as they are really interesting and well worth knowing about.

Exactly mimic the design of existing languages

TypeScript does not aim to simply copy the design of EcmaScript/JavaScript.

While it does indeed strictly respect the runtime behavior of JavaScript in order to remain a superset of the language, it does introduce its own syntax to let us achieve our goals with more expressiveness, clarity and type safety.

For instance, TypeScript generics don’t exist in EcmaScript, but give us means to create data structures, types and functions that are work safely with various types.

As a matter of fact, this non-goal of TypeScript is actually the basis of all the greatness of the language: fully respect the runtime, but improve the readability of the code, its robustness and the developer experience.

There countless examples of awesome features and syntactic sugar that TypeScript brings to the table and that greatly improve the developer experience (DX).

Aggressively optimize the runtime performance of programs

TypeScript does not try to emit super optimized JavaScript code.

What this non-goal means is that the code that the TypeScript compiler generates aims to be idiomatic JavaScript code; that is, code that remains consistent with JS best practices and that humans should still be able to decipher.

Don’t misinterpret this point though; performance is clearly not ignored by the TypeScript team, as proven once again recently by the 3.9 beta release notes.

Apply a sound or “probably correct” type system

Instead of focusing only on creating a provably (read mathematically) correct type system, TypeScript tries to find a balance between the correctness facet and the developer productivity.

Of course, as time goes by, the type system becomes more and more powerful, but at the same time, the developer experience is front and center, which reminds me of why I fell in love with Kotlin right away.

To me, TypeScript and Kotlin are two of the most enjoyable programming languages that I’ve been using.

Provide an end-to-end build pipeline

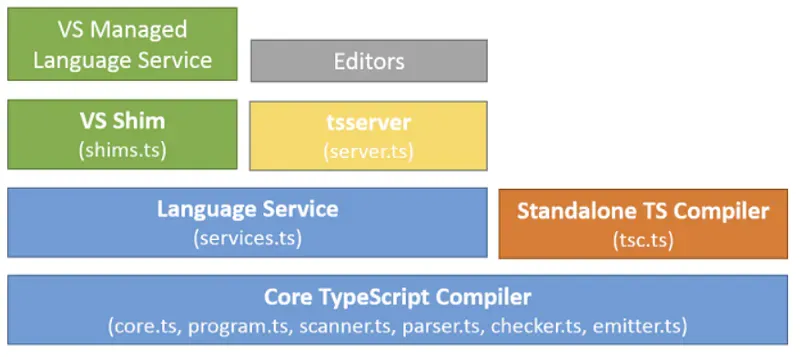

TypeScript does not aim to do everything itself. Instead, it tries to be open and easily extensible so that other tools can use the compiler easily and integrate it in editors, IDEs and build chains.

From the get go, TypeScript’s architecture has been defined so as to integrate nicely with as many build/development tools / IDEs as possible.

This is made possible by two pieces of the main architecture:

The first piece of interest is the language service, which complements the core compiler pipeline by providing support for familiar code editor features like auto-completion, colorization, code formatting, code refactorings, debugging/breakpoints, and tons more. You can learn more about it here.

The second piece of this puzzle that is of great importance is the TSServer, which wraps the core compiler as well as the language service and exposes those through a JSON-based protocol.

By exposing the compiler + language service features directly over JSON, IDE integration actually becomes a breeze for editor/IDE makers. Moreover, by directly integrating the compiler pipeline within the IDEs, they can all benefit from a great feature set right away.

Without this architecture in place, each editor / IDE would have to put much more effort into adding support for the language and there would be huge discrepancies across editors, which is not the case today thanks to TypeScript’s design. N-e-a-t!

If you want to look at an example, then check out how VSCode integrates TypeScript support (btw, VSCode itself is written using TypeScript, a great example of the ‘eat your own dogfood’ principle :p).

Of course, the TSServer also makes it easy to interact with the compiler in build tools / build chains, which opens up a world of possibilities.

Add or rely on run-time type information in programs, or emit different code based on the results of the type system

This is one of the non-goals of TypeScript that I’m a bit sad about.

This one means that TypeScript does not aim to push its type information up to runtime or even to let us keep type metadata at runtime.

The design choice of TypeScript is to help us developers as much as possible at development time and to limit/try to eliminate our need for runtime type safety. I guess that the idea is “simply” that if we can have enough certainties at compile time, then the case for runtime type safety is not that big.

In practice though (IMHO), there are scenarios in which runtime type safety is really beneficial. For one, when we receive data from back-ends or external clients, it’s often useful to be able to assert that types are as expected. This is not something that the TypeScript language aims to help us with.

It doesn’t mean that it is impossible though. I’ll write about some solutions like io-ts later on (hint: there are plenty).

Provide additional runtime functionality or libraries

TypeScript does not provide specific runtime functionality through extensions/libraries.

TypeScript exclusively focuses on compile time. From there, it generates EcmaScript compliant code, but that emitted code doesn’t rely on TypeScript specific elements at runtime; it is just JavaScript that will run in any ES runtime.

Introduce behavior that is likely to surprise users

Oh how I like this non-goal! It’s actually one of my favorites.

To summarize this one, let’s say that TypeScript is not a language for mathematicians, like Scala can be (oops, there, I just wrote it, sorry, not sorry!).

It might sound sad to some, but to me this is awesome. Programming languages should not (only) be made for actual scientists. Code should read like prose, not like equations.

The more readable and accessible a language is, the more chance there is to increase the accessibility of software development to the largest groups of people. Arcane syntax doesn’t help anybody.

Now that I’ve started teaching programming to my son, I certainly don’t plan on introducing him to languages like Scala that would just give him a bitter taste and push him to give up instead of having fun. Instead, I’ll teach him Python (for ease of use and simplicity), Kotlin and of course TypeScript!

TypeScript is great in this regard. Just do take a look at some TypeScript code and enjoy the beauty!

Conclusion

In this article, we quickly reviewed TypeScript’s non-goals, which are strongly tied to the success of the language that we can witness today.

By focusing on readability, developer experience, tooling integration and by applying the principle of least surprise, TypeScript has achieved something that (IMHO) few programming languages have: greatness and development pleasure. (Ubiquity is on the way, but give it some more time though! ;-))

That's it for today! ✨

About Sébastien

I am Sébastien Dubois. You can follow me on X 🐦 and on BlueSky 🦋.

I am an author, founder, and coach. I write books and articles about Knowledge Work, Personal Knowledge Management, Note-taking, Lifelong Learning, Personal Organization, and Zen Productivity. I also craft lovely digital products . You can learn more about my projects here.

If you want to follow my work, then become a member.

Ready to get to the next level?

To embark on your Knowledge Management journey, consider investing in resources that will equip you with the tools and strategies you need. Check out the Obsidian Starter Kit and the accompanying video course. It will give you a rock-solid starting point for your note-taking and Knowledge Management efforts.

If you want to take a more holistic approach, then the Knowledge Worker Kit is for you. It covers PKM, but expands into productivity, personal organization, project/task management, and more:

If you are in a hurry, then do not hesitate to book a coaching session with me: