How to use a proxy to bypass firewalls in corporate environments

In medium to large companies, it’s almost always the case that your Web traffic has to go through a corporate proxy to reach the Web. Here’s how to find out more about those proxies and how to use them from your tools and terminals

In medium to large companies, it’s almost always the case that your Web traffic has to go through a corporate proxy to reach the Web. Here’s how to find out more about the proxies.

In this article I’ll give you a few tips about how to discover which proxy/proxies is/are used (if any). I’ll also mention how more complex IT environments handle proxy settings using the automatic proxy discovery protocol (WPAD) and pac files, perform TLS termination and sometimes even only allow specific user-agents through. Finally, I’ll tell you how to configure your apps and command-line tools access the Web.

As we’ll see, in basic environments, you’ll just have to look at the settings to find the URLs/IPs/ports of the proxies. In more complex environments, you’ll need to analyze the pac file to find those out.

Why and a little warning

First of all, a word of advice: there are often strict security policies in place around network traffic in general. Make sure that you’re not doing something that goes against those policies. If you’re not sure, then ask the network / security team / CISO before doing anything that could put you in a bad spot.

There are multiple reasons for which you might want to know more about the corporate proxies being used. The first one might be curiosity, which may be the worst reason. Another one, more valid could be to be able to access the Web from your development tools and/or terminal.

Personally, I’ve often needed Web access to be able to download certain tools / download npm/maven/whatever packages, etc. And usually I want my tools to be doing that or at least to be able to do it from a terminal.

In any case, make sure to reach out to the security and network teams to see if there are established/accepted solutions to let you do what you want. Better safe than sorry ;-)

If you know what you’re doing, then keep on reading.

Some ways to find out which proxies are used

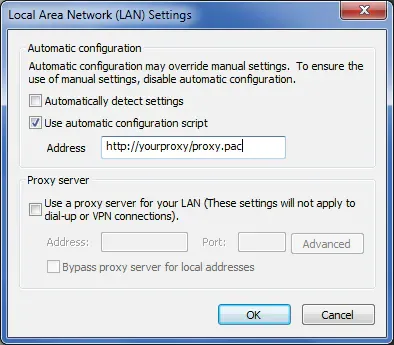

Some “basic” environments simply enforce a proxy (or set of proxies) through the system configuration (usually defined/enforced through group policies and the like in Windows environments), which can be checked out through Internet Explorer (meh):

You’ve probably already seen this Window at least once in your life ;-)

To reach that screen, you can look at this Microsoft KB article: https://support.microsoft.com/en-ph/help/4551930/using-proxy-servers-together-with-internet-explorer

For Edge, look at this article: https://www.windowscentral.com/how-set-proxy-edge-windows-10

If you can directly see the proxy settings through any of the above, then you’re done, there’s probably no need to look further; just grab the hosts/ips/ports.

Another way if you’re on Windows 10 is to look at the Proxy settings through the Settings app of the OS, as described here: https://helpdeskgeek.com/networking/internet-connection-problem-proxy-settings/ (that the article also covers how to discover the proxy settings for OSX & Linux).

In Google Chrome, you might be able to access this settings page:

chrome://net-internals/#proxy

In Mozilla Firefox, you can see the same through:

about:preferences#advanced

If you have access to the Windows registry, then it’s dead easy; just look at the following key: HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings.

Or through the command line:

reg query "HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings" | find /i "proxyserver"

If you’re admin on the machine (which you should probably never be!), then you can also run the following command as administrator: netsh winhttp show proxy.

If you want to get fancy, you can get the same information through PowerShell: Get-ItemProperty -Path 'HKCU:\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings' | findstr ProxyServer

Proxy auto-config (PAC)

Proxy Auto-Config (PAC) files are (not so) magical files describing the rules for letting a Web browser (and other user agents) select which proxy server to use for a given URL.

When a Web Browser is configured to use a PAC file then, whenever it needs to access the network, it invokes the FindProxyForURLfunction defined in the pac file in order to determine the proxy server to use (if any).

Usually, companies that enforce traffic to go through proxies define a PAC file that instruct user agents to either connect directly to the target (e.g., for internal IP ranges / internal DNS domains), or to connect through specific proxies otherwise.

In such environments, the PAC file is really what you’re after; it contains all of the information you need.

Here’s an example PAC file, taken from here:

function FindProxyForURL(url, host) {

// If the hostname matches, send direct.

if (dnsDomainIs(host, "intranet.domain.com") ||

shExpMatch(host, "(*.abcdomain.com|abcdomain.com)"))

return "DIRECT";

// If the protocol or URL matches, send direct.

if (url.substring(0, 4)=="ftp:" ||

shExpMatch(url, "http://abcdomain.com/folder/*"))

return "DIRECT";

// If the requested website is hosted within the internal network, send direct.

if (isPlainHostName(host) ||

shExpMatch(host, "*.local") ||

isInNet(dnsResolve(host), "10.0.0.0", "255.0.0.0") ||

isInNet(dnsResolve(host), "172.16.0.0", "255.240.0.0") ||

isInNet(dnsResolve(host), "192.168.0.0", "255.255.0.0") ||

isInNet(dnsResolve(host), "127.0.0.0", "255.255.255.0"))

return "DIRECT";

// If the IP address of the local machine is within a defined

// subnet, send to a specific proxy.

if (isInNet(myIpAddress(), "10.10.5.0", "255.255.255.0"))

return "PROXY 1.2.3.4:8080";

// DEFAULT RULE: All other traffic, use below proxies, in fail-over order.

return "PROXY 4.5.6.7:8080; PROXY 7.8.9.10:8080";

}

Don’t hope too much for the JS code quality here; usually you’ll stumble upon code written by people who aren’t Web developers and who couldn’t care less ;-)

What you want to decipher in the pac file is the proxy (or proxies) that you should be using for your own purposes. For instance, if you want to be able to access the Web, and not some internal site/domain, then you probably need to use 4.5.6.7:8080 and/or 7.8.9.10:8080.

Depending on who is maintaining the PAC file, this may be super clear or super cryptic (some sysadmins make a real mess of those files).

But how do you find the pac file? Good question!

There are two possibilities; either the PAC file is directly set through the proxy settings, for example visible through IE:

In which case, again you have what you need.

Alternatively, the proxy settings are configured to be automatically detected. In that case, the WPAD protocol is used to find the PAC file.

Web Proxy Auto-Discovery Protocol (WPAD)

PAC files usually go in tandem with a protocol called WPAD, for Web Proxy Auto-Discovery Protocol.

As its name indicates, the WPAD protocol is used by Web browsers / user agents to automatically find out about the proxies to use, using DHCP and/or DNS.

Briefly explained, WPAD works by trying to download a file called “wpad.dat”, from the “wpad” host.

The easiest way to check if WPAD is used in the environment is to try a simple ping:

ping wpad

If that doesn’t exist, then either WPAD is not used, or you need to append an environment specific DNS suffix, which you should be able to identify through ipconfig /all , as explained here. Basically you’re looking for the Primary DNS suffix & DNS Suffix Search List.

If you can access wpad or wpad.<some suffix>, then you can download the wpad.dat file through:

http://wpad.<suffix>/wpad.dat

If you have that file, then bingo, you once again have the information that you’re after.

If that doesn’t work, then WPAD might get configured through DHCP, in which case you can either try to have a look at the DHCP traffic through a tool such as Wireshark, or try the method proposed here.

BTW, the Wikipedia article about WPAD mentions some facts around the security of WPAD; this is quite fun (or sad?) to read.

Proxy config

So, you have the proxy settings; now what?

Well it all depends on how/where you want to be using those. I’ll give you a few examples, but for the rest you’ll need to dig into the documentation of your tools ;-)

Bash

If you want to access the Web from you Bash terminal (and oh I feel you!), then you need to configure (some or all of) the following environment variables:

export HTTP_PROXY="http://<username>:<password>@<host>:<port>

export HTTPS_PROXY="http://<username>:<password>@<host>:<port>

export FTP_PROXY="http://<username>:<password>@<host>:<port>

export SOCKS_PROXY="http://<username>:<password>@<host>:<port>

export TELNET_PROXY="http://<username>:<password>@<host>:<port>

export ALL_PROXY="http://<username>:<password>@<host>:<port>

export NO_PROXY="localhost,127.0.0.1, <whatever else>"

As you can see above, you can also define the credentials to use to authenticate against the proxy. For some environments, you have to use your Windows domain credentials.

Git

If you use Git from your Bash terminal (haha), then you’re good to go.

If not, then you might need to configure git to use the proxy:

git config --global http.proxy http://<username>:<password>@<host>:<port>

Again, the username/password is optional; it all depends on the environment.

These settings will be stored in your home folder’s “.gitconfig” file.

Don’t hope too much if you want to use git over SSH though..

npm

With npm, it’s also straightforward to configure the proxy to use:

npm config set proxy http.proxy http://<username>:<password>@<host>:<port>

npm config set https-proxy http.proxy http://<username>:<password>@<host>:<port>

These settings will be stored in your home folder’s “.npmrc” file.

Maven

With Maven, everything goes through the “settings.xml” file, as usual:

<proxies>

<proxy>

<host>http://<host></host>

<port><port></port>

<username>...</username>

<password>...</password>

<nonProxyHosts>...</nonProxyHosts>

</proxy>

</proxies>

Check out this article for more details.

Self-signed certificates

In many organizations, corporate proxies also do SSL/TLS termination. That is, the corporate proxy and surrounding infrastructure terminate the SSL/TLS connections at the edge so that they can inspect all of the traffic. I hope you were aware of this while surfing at work, or you might feel bad now ;-)

Organizations that do this usually present self-signed (but internally trusted) certificates to the client machines, while checking the third party certificates on their side.

This means that if you’re trying to go to https://gmail.com, then you will never see the certificate of gmail.com. Instead, you’ll see a certificate that has been created/self-signed on the fly by the corporate infrastructure.

This works fine in the corporate Web browsers because your machine is configured to trust those certificates. But it won’t be the case for your tools and terminals.

If the environment does this, then you’ll need to make sure that the certificates that you receive are accepted/trusted by your tools/terminals. This is super bad for security, but it’s the only way (that I know of).

This is a bit of our scope of this article, but if you’re facing this, then try to see if those self-signed certificates are all emitted by the same Root CA. If that’s the case, then only trust that root certification authority in your tool.

If each certificate is completely independent, then bummer, you’ll need to disable certificate checks.

For instance, with npm, you can use the following to trust a specific CA certificate file:

npm config -g set cafile blabla.cert

If you’re unlucky and not scared of getting hacked (hint: you should be!), then you might want to do this instead:

npm config -g set strict-ssl false

With Git:

export GIT_CURL_VERBOSE=1 # to debug

export GIT_SSL_NO_VERIFY=1

There are similar options for most tools out there that deal with SSL/TLS.

User agent string

Sometimes, proxies are strict about which user agents can go through or not. This is certainly a bad practice in 2020 (and it’s been one for a long time), but be aware of this.

If that’s the case, then determine which user-agent string is accepted (probably the one of the main/vetted Web browser), and adapt your tools to use that user agent string.

You can also go a step further and install your own local proxy (e.g., using Squid, privoxy and the like) to automatically modify your HTTP requests before letting them out to the corporate proxy.

But this is a tad more advanced :)

Conclusion

In this article, I’ve explained how you can identify the corporate proxies that are being used and how to configure your tools/terminals to connect to the Web through those.

I’ve also told you about PAC files and the WPAD protocol which are often used.

Finally, I’ve explained that some organizations do SSL/TLS termination, present self-signed certificates and might even be evil and only allow specific user-agents to pass through.

Hopefully you won’t need to do any of the above, but if there’s no choice and no help available, this might prove useful.

That's it for today! ✨

About Sébastien

I'm Sébastien Dubois, and I'm on a mission to help knowledge workers escape information overload. After 20+ years in IT and seeing too many brilliant minds drowning in digital chaos, I've decided to help people build systems that actually work. Through the Knowii Community, my courses, products & services and my Website, I share practical and battle-tested systems. You can follow me on X 🐦 and on BlueSky 🦋.

I am an author, founder, and coach. I write books and articles about Knowledge Work, Personal Knowledge Management, Note-taking, Lifelong Learning, Personal Organization, and Zen Productivity. I also craft lovely digital products.

If you want to follow my work, then become a member and join our community.

Ready to get to the next level?

If you're tired of information overwhelm and ready to build a reliable knowledge system:

- 🎯 Join Knowii and get access to my complete knowledge transformation system

- 📚 Take the Course and Master Knowledge Management

- 🚀 Start with a Rock-solid System: the Obsidian Starter Kit

- 🦉 Get Personal Coaching: Work with me 1-on-1

- 🛒 Check out my other products and services. These will give you a rock-solid starting point for your note-taking and Knowledge Management efforts