How to Split Long Notes into Atomic Notes: A Comprehensive Guide

A comprehensive guide on splitting long notes into atomic notes within a Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) system, highlighting the benefits, and practical steps

In this article, I want to share ideas about how to split long notes into atomic ones. This practical guide should help you enhance your Knowledge Management practices.

Introduction

The concept of atomic notes deserves more attention from those seeking to create more valuable notes that optimize their information retention/retrieval processes and enable connecting ideas together (i.e., create valuable Knowledge Graphs).

As we'll see, atomic notes are much more interesting than long and linerar ones.

The Downsides of Long Notes in Personal Knowledge Management Systems

While long notes are sometimes useful or unavoidable, their drawbacks in the context of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) systems are clear. They hinder quick retrieval, contribute to cognitive overload, impede the creation of a connected knowledge network, limit the system's flexibility, and are less suitable for sharing.

PKM systems are designed to enhance the way we capture, organize, retrieve, and use knowledge. The ultimate goal is to create a dynamic ecosystem of information that supports learning, decision-making, and creativity. However, incorporating long notes into a PKM system can introduce several challenges that may compromise its usefulness, effectiveness and efficiency.

Here are some of those challenges:

1. Makes it harder to retrieve information

Long notes, by nature, tend to contain multiple ideas, insights, and pieces of information clustered together and intertwined. This density can make it difficult to quickly find specific pieces of information when they're needed.

2. Leads to Cognitive Overload

A core principle of effective PKM is minimizing cognitive overload by organizing information in a way that aligns with how our brains naturally process and retrieve data.

Long notes, with their complex and often convoluted structures, can quickly become overwhelming. They make it much harder to absorb and recall information. This is counterproductive to the learning and creative processes that PKM systems aim to support.

3. Impedes Linking and Connectivity

One of the strengths of a robust PKM system is the ability to create connections between different pieces of knowledge. Long notes make it challenging to establish these links because they blur the lines between distinct ideas, making it hard to see how they relate to other concepts within the system.

Atomic notes, on the other hand, facilitate creating a network of interconnected ideas, enhancing understanding and discovery.

4. Limits Flexibility and Adaptability

While long notes and documents are generally able to express complex ideas in a linear way, they're far from ideal.

PKM systems thrive on flexibility and the ability to evolve over time. Long notes are static and rigid. They don't easily allow for the addition, modification, or reorganization of information. This rigidity can stifle the growth of your knowledge base and limit its adaptability to new insights or changing needs.

Isn't there a way to take Smarter Notes?

At this point, we can probably agree that long notes and documents are far from ideal from a Knowledge Management perspective. Still, it's all we get taught. At school we're only taught the basics of linear note-taking, writing essays and summarizing information. It's no wonder that the default for most people is to reuse the same approaches throughout their lives...

But there really is a better way. Taking smart notes consists in going from linear notes that explore ideas in the form of chapters, sections, subsections and paragraphs to atomic/networked notes. Atomic are short and focused notes that each explore specific topics/ideas and are connected to each other. Atomic/networked notes form a network of notes, also known as a Knowledge Graph (KG).

You might be puzzled about how to create and navigate such a graph. Well, my goal is to help you better understand how to create yours, and how to leverage it.

By the way, Sönke Ahrens has written a fantastic book called How to Take Smart Notes, explaining these ideas, among others. I strongly recommend you to give it a read:

I just want to clarify one point before we continue: it's not because you create a Knowledge Graph that you can't also create and maintain linear "versions" of the information or notes dedicated to giving a more linear way of exploring it (e.g., Maps of Content).

Understanding Atomic Notes

Atomic notes are specific, concise, self-contained and context-independent pieces of information (i.e., notes).

Creating atomic notes is quite different from traditional linear note-taking. Before diving into the process of creating such notes, it's crucial to grasp their core characteristics:

- Specificity: Each note should cover a single idea

- Conciseness: Atomic notes should remain easily "digestible". When an atomic note becomes too long, you should consider splitting it up in smaller (i.e., more atomic) pieces

- Independence: Notes should be understandable on their own, without needing to refer to other notes.

- Linkability: Despite their independence, atomic notes intend to easily be connected to related notes in order to build a Knowledge Graph

To learn more, check out my previous article on this topic:

How to Split Long Notes

Splitting long notes into atomic notes involves several steps. The first idea is that a long note is nothing more than a linear series of "LEGO blocks" that can be separated, rearranged, and connected to each other. Each part can become a separate note, linked to closely or loosely related ones.

1. Identify Core Ideas

Begin by reading through your long note to identify its core ideas or concepts.

Look for natural divisions in the content, such as different topics, subtopics, or themes. Highlight or underline these sections as potential candidates for atomic notes.

2. Create Individual Atomic Notes for Core Ideas

Start by creating atomic notes for each core idea you have identified. Those first notes will explain the ideas from first principles (i.e., complete independence), laying out a solid foundation for the next ones.

Now, repeat the process for all the other ideas. During this first pass, just focus in isolating the ideas and avoiding to cover multiple ideas within a single note.

The title of the notes you create should clearly reflect the specific idea or concept it describes. Be concise yet descriptive enough to understand the note's content at a glance. Think of the note title as a sentence or part of sentence that you might want to include somewhere else.

Check out my article about how to name your notes:

3. Refine for Clarity and Independence

Ensure each atomic note is written clearly and contains enough context to be understood independently. This may involve adding brief explanations or definitions that were implied in the original long note but not explicitly stated. If you can't add enough context to clarify, then you might need to further decompose the note, until you get to really specific ideas that you can more easily explain.

4. Link Related Notes

One of the powers of atomic notes lies in their interconnectivity. Use your note-taking tool's linking feature to connect related atomic notes. This network of notes not only facilitates navigation but also helps in understanding the relationships between the different pieces of the puzzle.

Linking is more art than science, but the idea is straightforward: if you think that another note is related to the current one or is at least interesting to mention, then add a link to it.

5. Add Metadata

Take some time to add metadata to each new note you create. I personally use tags a lot. Those help me find what I need more easily, for instance by using combination of tags. Those also enable me to more easily create and maintain Maps of Content (MoCs).

Don't worry too much about the taxonomy you use at the beginning. Just try to reuse existing tags if possible. Some tools such as Obsidian facilitate this.

I've previously shared tips about how to tag your notes:

6. Review your notes

After splitting, organizing and adding metadata to your notes, take the time to review those for coherence, clarity, completeness, and redundancy. Make adjustments as needed to ensure each note stands on its own while still contributing to the broader knowledge base.

7. Consider creating a Map of Content (MoC)

Once you're done creating your Knowledge Graph, it may be useful to create a Map of Content to ease your (future self) way into the Knowledge you've just organized.

Maps of Content are useful because they provide yet another way to resurface useful notes in specific contexts. They're also useful tools to think about the "network" as a whole.

Check out my article about MoCs to learn more:

Concrete Example

Now that you have the "framework" to use, let's look at a more concrete example based on my own notes.

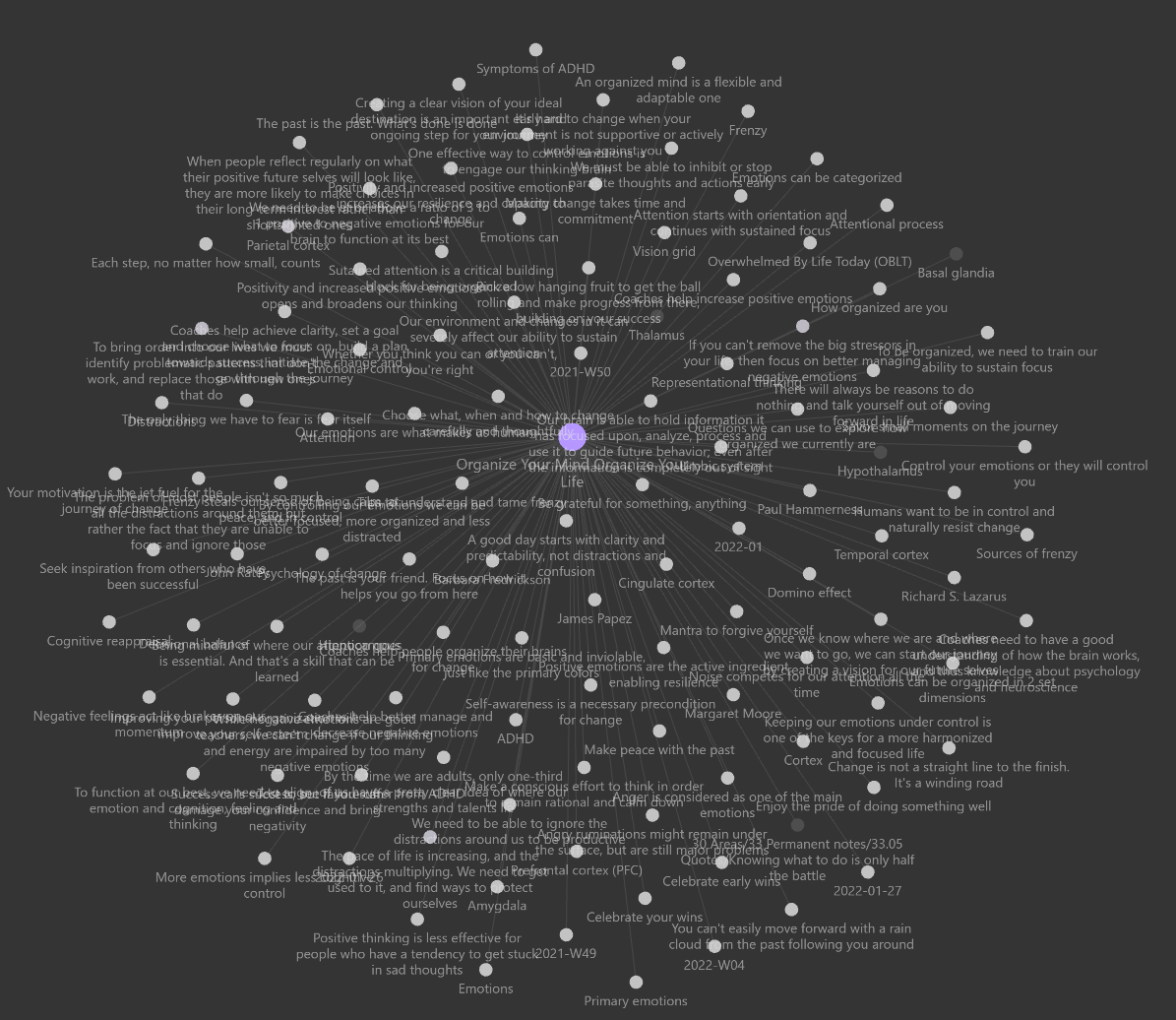

While reading the book called "Organize Your Mind Organize Your Life" by Paul Hammerness and Margaret Moore, I have created a summary of the things that resonated with me:

That is just the very first part. That note is actually very long. It covers all the chapters of the book. If you look closely at that note, you'll notice that it actually contains a lot of information that I have captured, but also that it includes many links to other notes (links in Obsidian are recognized by the brackets (i.e., "[" and "]") around. While that note is a really long one, it also serves as a Map of Content for the book in my knowledge graph. That's why I keep it around.

While I read books, I tend to create really long notes and then apply the process I've described in this article to extract the ideas that resonated with me into separate atomic notes that I connect to my Knowledge Graph. Once I'm done, the book summary becomes a map of the content I have extracted into a graph of atomic notes.

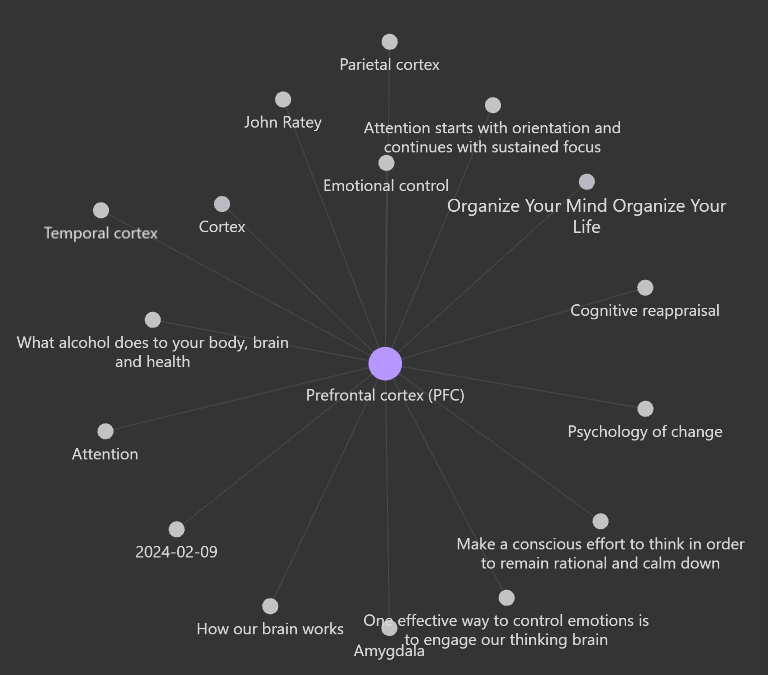

Let's look at one of the atomic notes that I have extracted from the initial document:

As you can see, I have created an atomic note that shortly discusses the Prefrontal cortex (PFC). That note includes the information I found in the book, and links to other notes in my knowledge graph. The ability to link that concept to others is really where atomic notes shine:

Those are the outgoing links of that note. So, after reading that book and extracting atomic notes from my summary, I have connected it with other ideas. And over time, those connections will only increase.

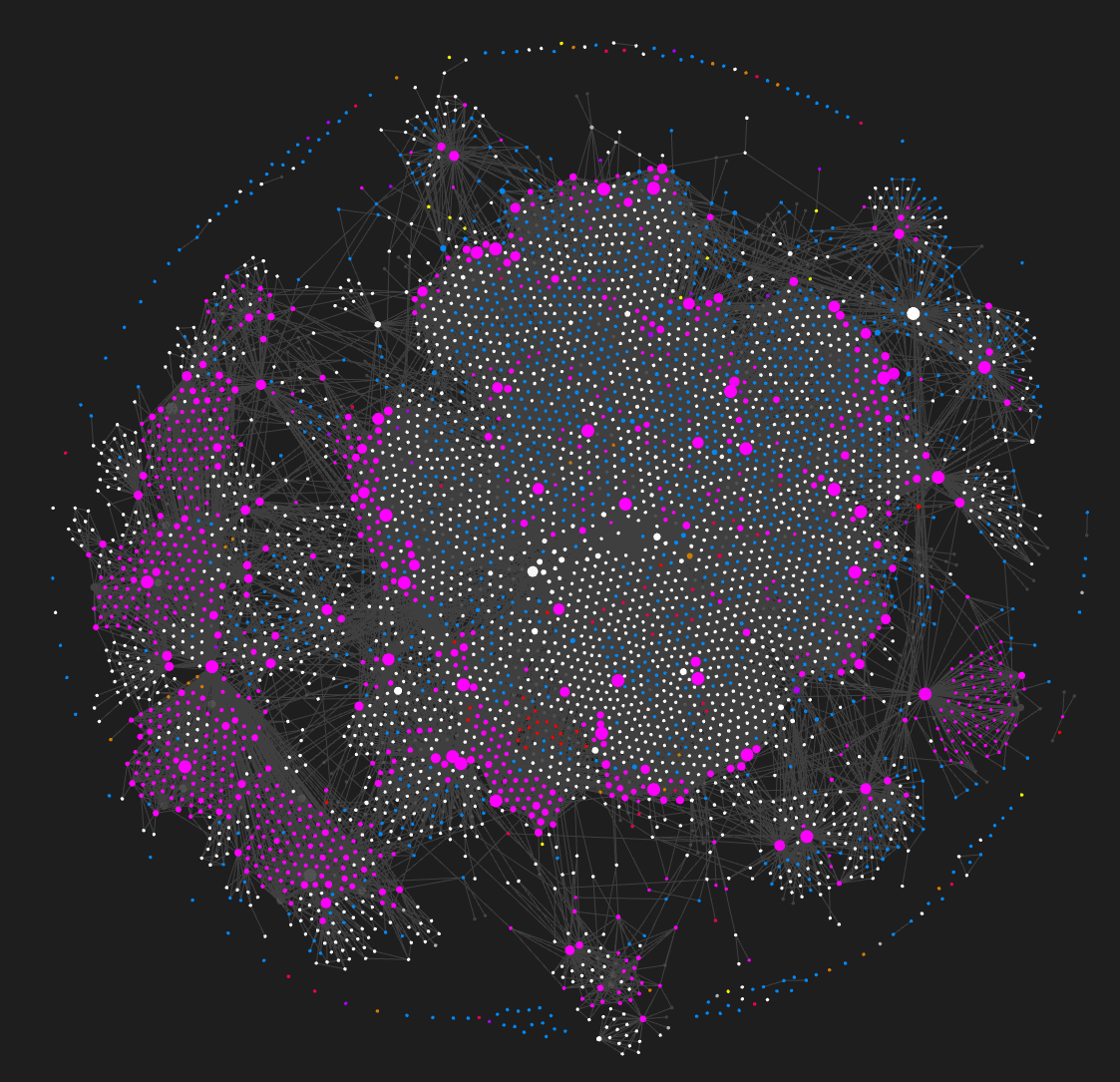

This is just one example, but it should already give you an idea about how I go about it. Within the long note that I keep around, I don't mind duplicating information. I like the idea of the remaining long-form document to still be usable on its own, even though the most important part for me is feeding my Knowledge Graph:

As you can see, I've turned one long note into a useful graph of knowledge. And now, I get to connect all those separate pieces to other ideas I capture over time, further compounding the value of my personal knowledge base.

Conclusion

The transition from long-form note-taking to creating and connecting atomic notes can significantly impact your efficiency and effectiveness in handling information. By breaking down complex or extensive notes into smaller, interconnected pieces, you not only improve the accessibility of your knowledge but also enhance your ability to think critically and make connections between ideas. Embracing the atomic notes approach is a step toward much more dynamic and flexible knowledge management, where insights are not buried under the weight of words but are instead readily available at your fingertips.

About Sébastien

I am Sébastien Dubois. You can follow me on X 🐦 and on BlueSky 🦋.

I am an author, founder, and coach. I write books and articles about Knowledge Work, Personal Knowledge Management, Note-taking, Lifelong Learning, Personal Organization, and Zen Productivity. I also craft lovely digital products . You can learn more about my projects here.

If you want to follow my work, then become a member.

Ready to get to the next level?

To embark on your Knowledge Management journey, consider investing in resources that will equip you with the tools and strategies you need. Check out the Obsidian Starter Kit and the accompanying video course. It will give you a rock-solid starting point for your note-taking and Knowledge Management efforts.

If you want to take a more holistic approach, then the Knowledge Worker Kit is for you. It covers PKM, but expands into productivity, personal organization, project/task management, and more:

If you are in a hurry, then do not hesitate to book a coaching session with me: